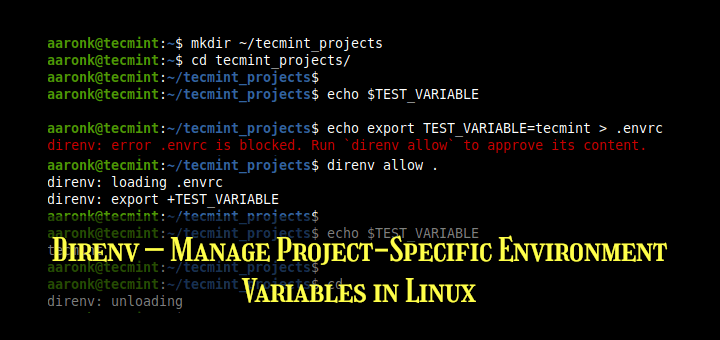

Direnv is a powerful command-line tool designed to manage environment variables dynamically based on the current working directory. It automatically loads and unloads environment settings when users navigate between projects, ensuring that each directory maintains its isolated configuration without cluttering the global shell environment. This functionality is particularly valuable for developers working across multiple repositories, where different tools, languages, and dependencies require specific setups. By integrating seamlessly with various shells, direnv enhances productivity and reduces errors associated with manual environment adjustments.

In essence, direnv operates by monitoring directory changes and executing a local .envrc file if present, which defines the variables to be sourced. Its shell-agnostic design allows it to hook into popular Unix-like shells, making it accessible to a wide audience. This article delves into the shells supported by direnv, exploring installation, configuration, and practical usage for each, while highlighting its versatility across interactive and non-interactive environments.

Understanding Direnv and Its Role in Shell Ecosystems

Direnv emerged as a solution to the common pain point of environment management in development workflows. Created by Denis Korneev in 2013, it has evolved into a staple tool for programmers using version control systems like Git. The core principle is simplicity: upon entering a directory with a .envrc file, direnv evaluates it to export variables, and upon leaving, it cleans up those variables. This process is triggered by shell hooks, which are shell-specific integrations that enable direnv to intercept directory changes.

The tool’s strength lies in its minimal overhead and security features, such as requiring explicit approval for .envrc files via the “direnv allow” command. This prevents accidental execution of untrusted scripts. Direnv supports a broad range of shells, from traditional ones like Bash to modern alternatives like Fish and Nushell, ensuring compatibility across diverse user preferences and operating systems.

Historical Context of Direnv Development

Direnv’s development began with a focus on Bash, reflecting the dominance of that shell in Linux and Unix environments at the time. Early versions emphasized lightweight integration, avoiding the bloat seen in some plugin-heavy tools. Over the years, community contributions expanded support to other shells, driven by user demand for cross-platform usability. By 2019, with version 2.0, direnv introduced more robust hooks for Zsh and Fish, incorporating features like lazy loading to optimize performance.

This evolution mirrors the shell landscape’s shift toward user-friendly interfaces, where shells like Zsh gained popularity through frameworks like Oh My Zsh. Direnv’s maintainers prioritized backward compatibility while adding support for emerging shells like Elvish and Nushell, ensuring the tool remains relevant in contemporary development stacks.

Why Shell Support Matters for Direnv Users

Shell support is crucial because direnv must integrate at the prompt level to detect directory changes in real-time. Without proper hooks, users would face manual invocations, defeating the tool’s automation purpose. For instance, in multi-shell environments—common in containerized development—seamless switching between Bash and Zsh without reconfiguring direnv saves time and maintains consistency.

Moreover, different shells have unique syntax and extension mechanisms, requiring tailored hooks. Direnv’s comprehensive coverage minimizes friction, allowing users to adopt it regardless of their preferred shell. This inclusivity fosters a larger community, with shared .envrc examples adaptable across shells.

Core Supported Shells: Bash and Zsh

Bash and Zsh represent the foundational shells supported by direnv, catering to the majority of Unix-like system users. Bash, the default on many Linux distributions, offers reliable POSIX compliance, while Zsh provides advanced features like better autocompletion and theming. Direnv’s hooks for these shells are straightforward, ensuring quick setup and reliable operation.

Both shells benefit from direnv’s ability to export variables in a way that persists only for the session’s duration in the directory. This prevents variable leakage, a common issue in shared environments. Users often pair direnv with these shells in IDEs or terminals for streamlined workflows.

Configuring Direnv in Bash

To integrate direnv with Bash, users append a single line to their ~/.bashrc file: eval “$(direnv hook bash)”. This hook function is executed every time the shell starts or sources a new profile, setting up a trap on the DEBUG signal to monitor command execution and directory changes. The trap invokes direnv’s internal logic to check for .envrc files and load them accordingly.

Once hooked, direnv operates transparently. For example, in a project directory, creating a .envrc with “export DATABASE_URL=postgresql://localhost/mydb” and running “direnv allow” will make that variable available immediately. Upon cd out, direnv unloads it, restoring the original environment. This mechanism uses Bash’s export -n to unset variables, ensuring clean state transitions.

Advanced users can customize Bash’s hook by wrapping it in functions for conditional loading, such as only activating in certain paths. Performance-wise, the hook adds negligible latency, as direnv caches evaluations and only re-runs on actual changes. Troubleshooting common issues, like hook not firing, often involves verifying the eval command’s placement after other extensions, such as those from rbenv or nvm, to avoid interference.

Integrating Direnv with Zsh and Oh My Zsh

For Zsh, the hook is similarly simple: eval “$(direnv hook zsh)” added to ~/.zshrc. This leverages Zsh’s precmd and chpwd functions to detect directory shifts, calling direnv’s export mechanism. Zsh’s extensibility makes it ideal for direnv, especially with plugins that enhance prompt information, like displaying active environments.

Oh My Zsh users have an even easier path by adding “direnv” to the plugins array in .zshrc. This built-in plugin handles the hook automatically, sourcing direnv during initialization and integrating with themes for visual feedback, such as a status indicator in the prompt. For non-Oh My Zsh setups, the manual hook suffices, but users should restart the shell post-configuration to activate it.

In practice, Zsh with direnv excels in large monorepos, where subdirectories have nested .envrc files. Direnv respects the directory hierarchy, loading overrides as needed. Potential pitfalls include conflicts with other Zsh plugins; resolving them requires ordering the direnv hook last in .zshrc. Overall, this combination offers a polished experience for power users seeking customization without complexity.

Modern Shells: Fish, Tcsh, and Elvish

Direnv extends its reach to more specialized shells like Fish, Tcsh, and Elvish, each bringing unique paradigms to environment management. Fish emphasizes user-friendly syntax and out-of-the-box features, Tcsh maintains C-shell traditions with history editing, and Elvish introduces a functional, scriptable approach. These hooks demonstrate direnv’s adaptability to non-POSIX shells.

Support for these shells involves custom integration points, such as Fish’s event system or Elvish’s module loading, ensuring direnv functions without disrupting native behaviors. This broadens direnv’s appeal to niche communities while maintaining core reliability.

Hooking Direnv into Fish Shell

Fish’s hook requires adding “direnv hook fish | source” to ~/.config/fish/config.fish. This sources a function that monitors directory changes via Fish’s event handlers, exporting variables from .envrc in a Fish-compatible format. Unlike Bash, Fish uses universal variables and lacks traditional exports, so direnv adapts by setting them in the current session scope.

Fish offers three modes via the direnv_fish_mode variable: eval_on_arrow for immediate triggering on navigation keys, eval_after_arrow for post-navigation, and disable_arrow for prompt-only evaluation. The default mode balances responsiveness and efficiency, ideal for interactive use. For instance, in a Node.js project, a .envrc defining “set -gx NODE_ENV development” loads seamlessly, unloading on exit.

Customization in Fish includes scripting around the hook for notifications or logging. Users report excellent performance, with direnv’s Fish integration avoiding the pitfalls of older tools that struggled with Fish’s non-standard syntax. If issues arise, such as variables not persisting, checking the source command’s execution order in config.fish resolves most cases.

Tcsh and Legacy Shell Integration

For Tcsh, the hook is eval direnv hook tcsh in ~/.cshrc. This uses Tcsh’s alias and eval mechanisms to intercept cd commands, invoking direnv’s logic. As a C-shell derivative, Tcsh requires backticks for command substitution, reflected in the hook syntax. This setup suits users in legacy environments, like certain BSD systems, where Tcsh remains default.

In operation, direnv exports variables using Tcsh’s setenv command within the .envrc evaluation. An example .envrc might contain “setenv PATH /project/bin:$PATH”, which direnv wraps for safe loading and unloading. The tool handles Tcsh’s history and editing features without interference, preserving user familiarity.

While less common today, Tcsh support underscores direnv’s commitment to backward compatibility. Advanced configurations involve aliasing cd to chain with direnv checks, enhancing reliability in scripted workflows. Troubleshooting focuses on ensuring the eval is not overridden by local .tcshrc files in projects.

Exploring Elvish Shell Support

Elvish (version 0.12 and later) requires generating a library file with “direnv hook elvish > ~/.config/elvish/lib/direnv.elv” and then “use direnv” in ~/.config/elvish/rc.elv. This modular approach aligns with Elvish’s design, where hooks are loaded as modules. The generated .elv file contains functions for directory watching and variable management, using Elvish’s fn syntax.

Direnv adapts to Elvish’s dynamic scoping by putting variables into the global namespace temporarily. A sample .envrc could use “put $EACH[0] = ‘value'” for array handling, but direnv standardizes it for export. This integration shines in Elvish’s REPL-like environment, allowing interactive testing of .envrc contents.

Elvish users appreciate the hook’s low footprint, as it leverages Elvish’s event system for efficient polling. Custom extensions, like integrating with Elvish’s prompt modules, can display direnv status. Common issues, such as module loading failures, are fixed by verifying the lib directory path.

Emerging and Specialized Shells: Nushell, PowerShell, and Murex

Direnv’s support for emerging shells like Nushell, PowerShell (pwsh), and Murex reflects its forward-looking design. Nushell treats data as structured streams, PowerShell brings Windows scripting to Unix, and Murex focuses on safe, typed shell scripting. These integrations use shell-specific event hooks or profiles.

This coverage enables direnv in cross-platform and data-oriented workflows, where traditional shells fall short. Hooks here often involve more setup but yield powerful, environment-aware sessions.

Setting Up Direnv in Nushell

Nushell integration occurs in config.nu by adding a hook to the env_change.PWD event: if (which direnv | is-empty) { return }; direnv export json | from json | default {} | load-env. This JSON-based export allows Nushell to parse and load variables as records, fitting its structured data model.

Upon directory entry, the hook exports .envrc variables into Nushell’s environment, unloading via a similar mechanism on exit. For example, a .envrc with “export API_KEY=secret” translates to a JSON object that Nushell loads as $env.API_KEY. This approach excels in data pipelines, where direnv manages tool-specific vars like database connections.

Nushell’s hook supports customization through nu_scripts for dynamic adjustments. Performance is optimized since JSON parsing is native and fast. Users transitioning from Bash find this hook intuitive, though verifying the “which direnv” check prevents errors in non-direnv environments.

PowerShell (pwsh) Hook Configuration

PowerShell users add Invoke-Expression “$(direnv hook pwsh)” to their $PROFILE script. This hook registers a prompt function that calls direnv on directory changes, using PowerShell’s environment provider to set variables. It supports both Windows and cross-platform pwsh, making direnv viable in .NET or Azure devops scenarios.

In action, direnv evaluates .envrc and uses Set-Item -Path Env:VARNAME -Value “value” internally. Unloading reverses this with Remove-Item. A practical use is in a PowerShell project with “export PSModulePath ./modules;$env:PSModulePath”, loading custom modules per directory.

The hook integrates with PowerShell’s ISE and VS Code terminals seamlessly. Advanced scripting can wrap the hook in try-catch for error handling. Issues like profile sourcing failures are resolved by reloading the profile or checking execution policy.

Murex Shell Integration

For Murex, add “direnv hook murex -> source” to ~/.murex_profile. Murex’s pipe-based syntax and type safety make this hook pipe the output directly into the shell’s source command, loading variables as typed assignments.

Direnv leverages Murex’s -> operator for redirection, ensuring clean integration. An .envrc example: “export DEBUG=true” becomes a Murex set command. This suits secure scripting environments, where direnv’s approval system aligns with Murex’s safety features.

Customization includes Murex functions around the hook for logging. The setup’s simplicity belies its power in handling complex types, like arrays, via direnv’s export. Troubleshooting involves confirming the profile loads, as Murex’s modularity can isolate configs.

Non-Interactive and Specialized Environments

Beyond interactive shells, direnv supports non-interactive contexts like JSON exports for scripting, Vim for editor integration, GitHub Actions (gha) for CI/CD, gzenv for Go workspaces, and systemd for service management. These extend direnv’s utility beyond terminals.

JSON mode allows piping “direnv export json” into parsers, useful in automation. Vim hooks load .envrc vars into sessions, enhancing plugin behaviors. GHA integrates via actions, setting env for workflows. Gzenv targets Go modules, and systemd uses direnv for unit files.

JSON and Scriptable Exports

The JSON shell in direnv outputs environment diffs as JSON objects, ideal for non-shell scripts. Command: direnv export json, producing {“added”:{“VAR”:”value”}}. This format enables integration with languages like Python or Node.js, where os.environ updates can mimic shell loading.

In CI pipelines, scripts parse this JSON to set vars before running tests. Advantages include portability across platforms without shell dependencies. Limitations: no automatic unloading, requiring manual cleanup in long-running processes.

Examples abound in Dockerfiles or Ansible playbooks, where direnv stdlib functions generate JSON for templating. Security-wise, JSON avoids eval risks, making it safer for untrusted .envrc.

Vim and Editor-Specific Hooks

Direnv’s Vim support uses a hook that sources .envrc upon opening files in a directory, setting Vim’s environment variables. Add to .vimrc: let $DIRENV_HOOK=”vim”; then eval the export. This loads vars like $PATH for Vim plugins needing external tools.

In practice, for a LaTeX project, .envrc exports TEXINPUTS, enabling syntax checking without global changes. Unloading happens on buffer switch or Vim exit. This integration boosts editor efficiency, especially in remote sessions via SSH.

Customization via autocmds allows per-buffer loading. Compared to shell hooks, Vim’s is lighter, avoiding full shell spins. Issues like var persistence across tabs are handled by re-evaluating on focus.

CI/CD and System-Level Integrations: GHA, Gzenv, and Systemd

For GitHub Actions, gha mode exports vars as YAML-like env blocks in workflows. Use direnv export gha in steps to load .envrc dynamically. This automates testing environments per repo branch.

Gzenv targets Go workspaces, hooking into go env for module-specific vars. Command: direnv export gzenv, setting GOPATH equivalents. Ideal for polyglot Go projects.

Systemd support integrates via direnv in service files, exporting to Environment= directives. This manages vars for daemons, like database creds, reloading on config changes.

These modes shine in DevOps, reducing duplication. Challenges include permission handling in CI, resolved by allow commands in setup steps.

Advanced Usage and Best Practices Across Supported Shells

Leveraging direnv across shells involves stdlib functions like use flake for Nix or dotenv for .env files. Best practices include versioning .envrc in Git (with secrets in .gitignore) and using direnv reload for live updates.

Cross-shell consistency is achieved via portable .envrc syntax, relying on direnv’s export normalization. Performance tuning, like deny/allow whitelists, optimizes large repos.

Standard Library Functions and Extensibility

Direnv’s stdlib provides cross-shell functions: layout python for virtualenvs, use nix for flakes. These abstract shell differences, e.g., path_add in Bash vs. Fish’s set -p.

Extending via custom hooks allows shell-specific tweaks, like Zsh precmd integrations for prompts. Community extensions, like direnv-vim, build on core support.

Security Considerations and Troubleshooting

Always review .envrc before allowing, as direnv executes it with shell privileges. Use direnv deny for revoking. Common troubleshooting: hook misplacement causes silent failures; verify with direnv debug.

Shell-specific issues, like Fish mode mismatches, require config tweaks. Logs via DIRENV_LOG help diagnose.

Performance Optimization Tips

Cache .envrc hashes to skip unchanged dirs. For high-traffic shells like Zsh, disable verbose output. In CI, use –norc to speed hooks.

Conclusion

Direnv stands out for its extensive shell support, encompassing Bash, Zsh, Fish, Tcsh, Elvish, Nushell, PowerShell, Murex, and specialized modes like JSON, Vim, GHA, Gzenv, and systemd. This breadth ensures developers can maintain isolated environments regardless of their chosen interface, from traditional prompts to modern data shells. By starting with a simple hook integration, users unlock automated variable management that scales across projects, reducing setup time and errors in diverse workflows.

The tool’s evolution highlights its adaptability, with hooks tailored to each shell’s quirks—Bash’s traps, Fish’s events, or Nushell’s structured loads—while preserving core principles of security and efficiency. Whether in interactive sessions or CI pipelines, direnv’s comprehensive coverage fosters consistent practices, making it indispensable for professional development.